Race and the Media: How a New Generation Is Fighting Back

July 9, 2015 — Joseph Torres

“If what the white American reads in the newspapers or sees on television conditions his expectation of what is ordinary and normal in the larger society, he will neither understand nor accept the black American. By failing to portray the Negro as a matter of routine and in the context of the total society, the news media have, we believe, contributed to the black-white schism in this country.”

— 1968 report from the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, also known as the Kerner Commission

When it comes to race, there are so many lessons our nation has either failed to remember or willfully ignored.

Nearly 50 years ago, riots shook up our country as cities like Newark and Detroit burned following confrontations between the police and local Black residents.

To understand the roots of the unrest, President Lyndon Johnson created the Kerner Commission to study what happened, why it happened, and what could be done to prevent this kind of conflict from surfacing again.

And in its 1968 report, the commission found that discrimination and segregation “had long permeated much of American life,” threatening “the future of every American.”

It also found that the media contributed to the turmoil by neglecting to cover the “causes and consequences of civil disorders and the underlying problems of race relations.”

Now, nearly half a century later, it’s easy to question how much has really changed. Over the past year, police brutality has drawn national media coverage following the killings of unarmed Black men, women and children. And the subsequent protests have also grabbed the press’ attention.

But activists of color are troubled that so much of the reporting has framed protesters as criminals and failed to address the larger issues of systemic racism, such as the over-policing of communities of color.

The coverage of the killing of 25-year-old Freddie Gray in Baltimore — who died in April after suffering a spinal cord injury while in police custody — is but another recent example. Following a day of rioting in Baltimore following Gray’s funeral, many journalists called the protesters “thugs.”

As Rashad Robinson of Color Of Change wrote in May: “The news media has done nothing but smear and condemn protesters, rather than ask important questions about the systemic conditions that created this conflict.”

However, a new generation of racial-justice leaders — from Black Lives Matter organizers to immigration-rights activists — is using the internet and social media to challenge traditional media’s stereotypical coverage of their communities.

At the same time, they’re urging the media to pay greater attention to Black women, Latinx people and Indigenous communities, who have also been victims of police brutality but whose stories often go untold.

And perhaps unexpectedly they’ve played a key role in policy debates over the future of the open internet, safeguarding the structures that will be critical to any effort to challenge and change the media narrative on race — so we’re not repeating the same stories 50 years from now in the ongoing fight for racial justice.

The police and the press: controlling the narrative

The fight for just and equitable media is essential to any struggle for racial justice. It’s much harder for injustice to prevail without the support and participation of a popular press.

This is why the publishers of Freedom’s Journal, the first Black newspaper in our country, wrote in its inaugural issue in 1827: “We wish to plead our own cause. Too long have others spoken for us. … From the press and the pulpit we have suffered much by being incorrectly represented.”

Throughout history, people of color have struggled to make their voices heard as many mainstream media companies — if not most — have either supported or failed to challenge slavery, Jim Crow laws, the removal of Indigenous people from their land, lynching, the internment of Japanese citizens and residents, the deportation of millions of undocumented immigrants, the targeted surveillance of Muslim Americans, and many other injustices and racist policies.

Over the past decade, a few newspapers have apologized for their role in supporting the killing of Black people or for failing to cover the civil rights movement.

Among those outlets is The News & Observer in Raleigh, N.C., which played a leading role in the 1898 riots in Wilmington that killed more than 60 Black residents.

More media companies should make amends

Instead of learning from past mistakes, the media continue to “get everything wrong that it seems to always get wrong and make the same fundamental mistakes,” says Dr. Jared Ball of Morgan State University’s School of Global Journalism and Communication in Baltimore.

And when it comes to coverage of racial unrest, says Tracie Powell, a writer and founder of All Digitocracy, one of those fundamental mistakes is allowing the police to control the narrative.

But the press has long relied on law enforcement when covering stories about riots or unrest. Just consider this passage from the Kerner Commission report and compare it to what’s happening in places like Baltimore today:

“Many people in the ghettos apparently believe that newsmen rely on the police for most of their information about what is happening during a disorder and tend to report much more of what the officials are doing and saying than what Negro citizens or leaders in the city are doing and saying.

“Editors and reporters at the Poughkeepsie [media] conference [hosted by the commission] acknowledged that the police and city officials are their main — and sometimes their only — source of information.

“It was also noted that most reporters who cover civil disturbances tend to arrive with the police and stay close to them — often for safety and often because they learn where the action is at the same time as the authorities — and thus buttress the ghetto impression that police and press work together and toward the same ends (an impression that may come as a surprise to many within the ranks of police and press).”

Nearly 50 years later, activists and journalists remain at odds over coverage of racial unrest.

Consider the recent CNN interview where host Brian Stelter challenged activist DeRay Mckesson for stating that the media presents the police narrative as accurate when that is often not the case:

STELTER: Are you saying the press should automatically assume the worst about the officers, about the authorities?

MCKESSON: I’m saying that there should be balance in the way that the critique is spread. And there isn’t. So, when I see news articles or when I see broadcasts that present the police narrative as true, so when they say things like …

STELTER: But it is oftentimes true, the police narrative.

MCKESSON: Is it true? I don’t know if it was true with Mike Brown. I don’t know if it was true with Rekia Boyd. Or I — maybe we differ on what ‘true’ means.

STELTER: But aren’t you talking about anecdotes, as opposed to the statistics? Are you saying the majority of statements by police officers in the U.S. are not true, public statements, press releases, etc.?

MCKESSON: What I’m saying is that the police are killing people and that they’re saying that it’s justified in every case, in a way that it just isn’t.

The interview captures the division that remains between how communities of color and a white-dominant press view coverage of race.

The failure to challenge the narrative

Tracie Powell is also critical of journalists who allow the police to control the story by accepting anonymous sources instead of demanding on-the-record interviews. “This goes against what journalism is all about,” Powell says. “We are falling down on the job.”

Powell cites CNN’s Don Lemon as a prime example.

In April, Lemon interviewed a family member of one of the six officers involved in the arrest and death of Freddie Gray. During the interview, CNN allowed the relative to tell the story from the perspective of the police without revealing her name and while obscuring her face. Lemon did little to challenge the narrative she presented.

Powell also points to South Carolina’s Post and Courier for its coverage of the shooting death of Walter Scott — a 50-year-old unarmed Black man — by a white police officer in North Charleston, S.C.

An initial story reported that Scott was shot while attempting to grab a Taser from the officer during a confrontation. The paper included Scott’s arrest history — made up mostly of failures to pay child support and failure to appear at court hearings.

Including this information contributes to the narrative that the officer was justified in fearing for his safety. The message from much of the coverage, Powell says, was that “these communities are bad and are filled with dangerous people who cause their own death.”

As the world now knows, a video that local resident Feidin Santana recorded on his cellphone showed that Scott was actually shot in the back while running away from the officer, who has since been arrested and charged with murder.

Likewise, Jared Ball is troubled that the media failed to challenge the origins of an online rumor that led to a confrontation between the police and students in Baltimore on April 27 — the day of Freddie Gray’s funeral.

According to press reports, the police responded to an online flyer that called for students to meet at the Mondawmin Mall in Northwest Baltimore at 3 p.m. to take part in a “purge,” a reference to a movie in which all crime is made legal for one night.

The police arrived in riot gear and closed down the nearby bus and train stations, which prevented area students from getting home.

The police have long harassed many students in that neighborhood, Ball notes, so law enforcement’s aggressive response turned a tense situation into a full confrontation, which ended in a day of looting and rioting.

The media changed the narrative, Ball says, without questioning the legitimacy of the online flyer or challenging the police response.

“A social-media scare produced a riotous spectacle and framed the remaining protest fraudulently,” he says.

Journalist Adam Johnson, who contributes to AlterNet and Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, attempted to uncover the origins of the purge flyer.

Johnson reached out through Twitter to the Baltimore Sun journalists who reported on the flyer during the afternoon of April 27. He asked them to provide information on who was responsible for circulating it, but they offered only a vague response.

Instead, another Sun reporter, who posted the flyer online, responded to Johnson on Twitter and said she first learned of the purge flyer from a Facebook friend.

Johnson searched online to find out who was responsible for calling for a purge.

Instead, he found examples only of people sharing the flyer on social media who were either indifferent to the rumor or condemned it. But none of this stopped the media from reporting on the flyer based on second- or third-hand hearsay, Johnson says:

“The problem with social media is that the reporters [feel] they don’t have to cite evidence. So the purge rumor just is. It’s a thing because everyone online says it’s a thing, but without citing the original post — either screen-capped or linked — along with the context with which it was presented, the reader is left thinking everyone sharing it is doing so in support.

“The way the original Sun reports were written, this was the distinct impression the reader was given.”

Reporting on the purge flyer in this manner heightened the climate of fear, which in turn allowed the police to take advantage of the situation by cracking down on protesters.

“Every single time that a trope is uncritically repeated by the media, by largely white media, I really personally believe it is heavily informed by racism because it conforms to a bias, ” Johnson says.

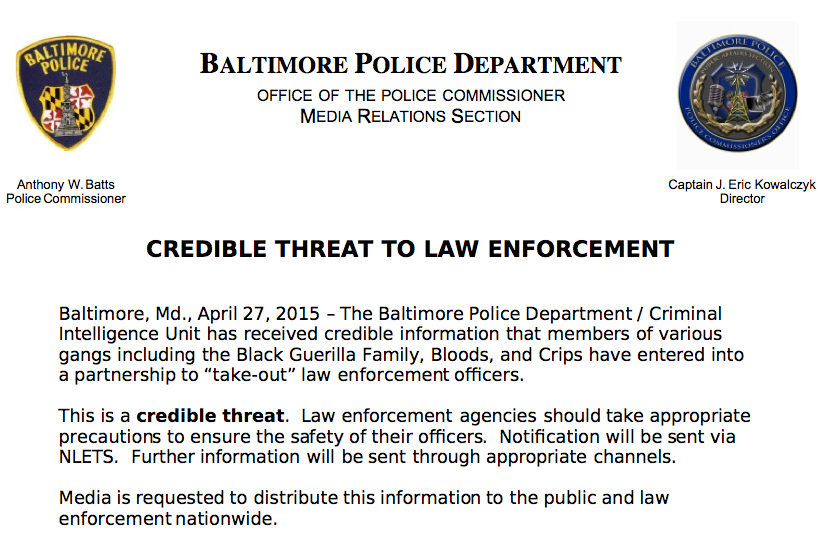

And as Zoë Carpenter reported in The Nation in April, the Baltimore Police Department used its Twitter account to spread “many pieces of information … that seemed to cross the line between public-safety information and propaganda.”

This included, Carpenter noted, a warning about “credible information” that Black gang members were planning to harm a police officer. The tweet linked to this press release:

The media then echoed this version of events. But gang members told reporters that they had agreed to a truce to protest police brutality.

Meanwhile, on June 24, VICE News reported on documents it had obtained from the Department of Homeland Security through a Freedom of Information Act request.

This material included a comment from a department employee who noted that the “FBI Baltimore has interviewed the source of this information [about gangs targeting police] and has determined this threat to be non-credible.”

The stone walls of white resistance

Coverage of the Freddie Gray protests serves as an important reminder that the mainstream media have historically portrayed people of color as threats to society.

In 1690, our nation’s first colonial newspaper, Publick Occurrences, referred to Indigenous people as “barbarous” and “savages.” In 1706, the Boston News-Letter said that Blacks were addicted to “Stealing, Lying and Purloining.”

Three hundred years later, the stereotypical coverage continues.

A 2011 Pew Research Center study of the Pittsburgh media market found that “African American males were present only rarely in stories that involved such topics as education, business, the economy, the environment and the arts. Of the nearly 5,000 stories studied in both print and broadcast, less than 4 percent featured an African American male engaged in a subject other than crime or sports.”

On a similar note, a recent report from Color Of Change and Media Matters found that Blacks appeared in crime stories on New York City TV stations at rates that eclipse the percentage of crimes they commit in the city.

The story isn’t much different for Latinx people. For years, studies by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists found that crime and immigration were the most dominant topics about the Latinx community that aired on the networks’ evening news.

Plenty of great journalists are doing their best to tell other stories about people of color. But too many reporters work for companies that claim to value diversity but don’t reflect that reality when it comes to hiring, the issues they cover, or the voices they amplify.

And even though several stories about systemic racism appeared in prominent outlets following the death of Freddie Gray, we shouldn’t expect the mainstream media to continue to cover these issues.

Instead, it will likely return to its old habits of covering race. As author and NPR TV critic Eric Deggans wrote in the spring edition of Nieman Reports:

“In my view, too often, coverage of racial issues at mainstream news organizations is treated episodically, focused largely on exploding controversies and breaking news stories. Someone is dead or is getting sued or has been arrested or has done something controversial, and media outlets are ready to track the fallout in stories almost guaranteed to rank at the top of their websites’ most-read list.

“But in my experience this approach also segregates the topic of race to news, focused on conflict and controversy, that polarizes audiences. Audiences are conditioned to see race as a hot-button topic only worthy of the most blockbuster stories, making it tougher for journalists to tell subtler, more complex tales.”

Just consider coverage of poverty. According to Pew, from 2007 to mid-2012, news stories primarily about poverty that appeared in 50 major media outlets made up just 0.2 percent of overall coverage. The failure to cover this issue occurred at a time when our country was going through a major economic crisis that widened the wealth gap between white households and Black and Latinx households.

And as journalist Dan Froomkin noted in Nieman Reports in 2013, there are overarching reasons that explain the media’s general resistance to covering poverty:

“The reasons for the lack of coverage are familiar. Journalists are drawn more to people making things happen than struggling to pay the bills; poverty is not considered a beat; neither advertisers nor readers are likely to demand more coverage, so neither will editors; and poverty stories are almost always enterprise work, requiring extra time and commitment.

“Yet persistent poverty is in some ways an accountability story — because, often, poverty happens by design.”

It’s important to note that many mainstream media companies have exposed injustices in our society during key moments in history. In the 1960s, for example, the major TV networks covered the brutal actions of white mobs and local police officers against civil-rights protesters during the fight to end segregation.

Nevertheless, the press hasn’t shown the same commitment to challenging systemic racism or its connections to structural inequality. This is why the Kerner Commission faulted the media for contributing to our nation’s racial unrest.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whose words are often co-opted by the media, addressed this issue in his 1967 book Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? King argued that support of historic civil-rights legislation among many white allies didn’t mean they supported racial equality:

”The outraged white citizen had been sincere when he snatched the whips from the Southern sheriffs and forbade them more cruelties. But when this was to a degree accomplished, the emotions that had momentarily inflamed him melted away.

”White Americans left the Negro on the ground and in devastating numbers walked off with the aggressor. It appeared that the white segregationist and the ordinary white citizen had more in common with one another than either had with the Negro.

”When Negroes looked for a second phase, the realization of equality, they found that many of their white allies had quietly disappeared. The Negroes of America had taken the President, the press and the pulpit at their word when they spoke in broad terms of freedom and justice.

”But the absence of brutality and unregenerate evil is not the presence of justice. To stay murder is not the same thing as to ordain brotherhood. The word was broken, and the free-running expectations of the Negro crashed into the stone walls of white resistance. The result was havoc.”

How the civil-rights movement helped change the media

Activists of color — as well as members of the Black and ethnic press — have long fought an unjust media system in the struggle for racial justice.

But few people are aware of the critical role the civil-rights movement played in challenging our nation’s media policies and system. It led to the first wave of journalists of color to integrate mainstream newsrooms during the 1960s and ’70s.

In Jackson, Miss., Black leaders worked with the United Church of Christ’s Office of Communication to challenge the license of a racist TV station run by a white supremacist. A federal court ruled in 1966 — for the first time in history — that U.S. citizens had the legal right to challenge a broadcast license.

This resulted in more than 340 license challenges against local broadcasters during the early 1970s. Black and Latinx groups led this effort in cities across the country.

This development forced media companies to desegregate their newsrooms and air more programming that was relevant to communities of color.

This activism also pushed the Federal Communications Commission to require broadcasters to engage with communities to determine their information needs and to hire employees that reflected the communities they respectively serve.

But many of those gains have since eroded. FCC rule changes have made it harder for communities to hold broadcasters accountable. And media consolidation — coupled with the changing media environment — has led to thousands of journalist layoffs over the past decade.

Industry statistics from 2015 show the number of journalists of color working at daily newspapers — 4,900 — is the same as it was in 1991. And the percentage of people of color working in the newsrooms of local TV stations (excluding Latinx-oriented outlets) declined to 19 percent in 2014.

Meanwhile, people of color still own just 3 percent of all full-power owned-and-operated TV stations and struggle to find investors for their online ventures.

But despite all of these inequalities, there are reasons for hope.

The power of the open internet

A new generation of activists is using the internet as a tool to chisel away at the “stone walls of white resistance” in the media’s coverage of communities of color.

“There is a reason why such a narrative is now being challenged and that is because of digital media,” says Julio Ricardo Varela, the founder of the online news site Latino Rebels. “You no longer have to rely on telling your story through traditional means whether it is a newspaper or a mainstream TV show; you are literally your own journalists, your own newsmaker, your own reporter.”

Powell is hopeful that the pressure the Black Lives Matter movement and other activists of color are placing on the press will make it harder for the media to ignore stories that need to be told.

And she points to citizen and community journalism exemplified by people like Feidin Santana, who recorded the video of the police officer shooting Walter Scott in the back.

“That young man is more valuable to journalism than Don Lemon is on any given day,” she says.

Meanwhile, Ball says the only bright spot he witnessed in the coverage of Baltimore was news produced by activists and alternative media via live-tweeting, live-streaming and posting audio clips, pictures and video on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

“They made the medium of the internet more valuable and relevant,” he says.

It’s no accident that the voices of marginalized communities can be heard online. Throughout history, a series of public-policy decisions enabled the internet to develop as a decentralized communications network largely free of corporate and government censorship.

Thanks to this open architecture, the internet has allowed marginalized communities to bypass traditional media and speak for themselves without needing to first seek permission from corporate gatekeepers.

In fact, the internet has given a new generation of activists the digital oxygen they need to help breathe life into their burgeoning movements.

But big internet service providers like AT&T, Comcast and Verizon have long tried to kill Net Neutrality, the principle that requires ISPs to treat all online traffic equally.

These companies want the power to censor, interfere with and discriminate against Web traffic, content and services. They want an online world where the rich pay more to ensure their content travels in the digital fast lane while the rest of us are relegated to the slow lane.

This would create a separate and unequal internet — making it harder for people of color to make their voices heard.

“Whether it’s the Movement for Black Lives, the Fight for $15, or an immigrant rights movement declaring ‘not one more,’ powerful 21st-century social justice movements require powerful communications platforms,” says Malkia Cyril, the executive director of the Center for Media Justice.

“Decentralized platforms lead to diverse leadership where every voice can speak and be heard,” Cyril says. “Democratic platforms allow decisions to be made and strategies to align across geography and issue. Nondiscriminatory platforms reduce the power of gatekeepers, and increase the power of those historically excluded. That’s why I fight to protect the internet, not simply because of what it is, but because of what it enables.”

All of this would go away without Net Neutrality. And in 2014, it appeared the big ISPs were going to get their way. These companies had convinced FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler, a former top lobbyist for the cable and wireless industries, to propose rules that would allow for internet fast and slow lanes.

It took a massive organizing effort to change Chairman Wheeler’s mind. And the voices of communities of color were critical to this effort.

The debate over Net Neutrality occurred at a pivotal moment.

A new generation of racial-justice activists representing the community’s growing political and moral consciousness demanded that the FCC protect the open internet. Many civil-rights groups and lawmakers of color joined this effort and made their voices heard.

And over the past five years, the Center for Media Justice, Color Of Change, Free Press and the National Hispanic Media Coalition have worked as part of a coalition — now called Voices for Internet Freedom — to fight for the digital rights of communities of color. Groups like 18 Million Rising and Presente.org have also been critical partners in advancing this goal.

The coalition organized town-hall meetings and rallies to engage the community and urge people to take action. Members of the Media Action Grassroots Network, a network of 175 community organizations that is a project of the Center for Media Justice, held Net Neutrality rallies in locations including Albuquerque (pictured), the Bay Area, New York City, San Antonio and Urbana-Champaign.

The coalition ensured that the new generation of racial-justice leaders would have their voices heard during the open-internet debate.

“It is because of Net Neutrality rules that the internet is the only communication channel left where Black voices can speak and be heard, produce and consume, on our own terms,” Patrisse Cullors, co-creator of Black Lives Matter, wrote last December in The Hill.

For years, the big phone and cable companies have relied on lawmakers of color and several legacy civil-rights groups to oppose any efforts that would ban ISPs from discriminating online. These companies claimed that Net Neutrality would broaden the digital divide. But this new group of leaders challenged that narrative.

In January 2015, a Center for Media Justice-led delegation of Black racial-justice leaders met with members of the Congressional Black Caucus and the FCC to discuss why Net Neutrality is essential to the fight against police brutality. The delegation included activists from Ferguson and Opal Tometi, a co-creator of Black Lives Matter.

Representatives from Black Lives Matter, the Center for Media Justice, Color Of Change, Ferguson and Free Press met with Rep. John Lewis during the height of the Net Neutrality debate.

During a meeting with Rep. John Lewis, the civil-rights icon pledged his continued support for Net Neutrality. He validated that the group stood on the right side of history when he said the civil rights movement would have accomplished even more had an open internet existed in the 1960s.

A few weeks later, the National Hispanic Media Coalition and Presente.org, in partnership with the Center for Media Justice, brought a delegation of Black, Latinx, Asian American and Native American activists to meet with key lawmakers of color and take part in a standing-room-only briefing with congressional staffers on Net Neutrality and racial justice.

By the time the FCC was gearing up for its vote, more than 100 racial-justice and civil-rights groups had signed a letter calling on the agency to adopt strong and enforceable Net Neutrality rules.

This collective effort not only inspired members of Congress to speak out, but it kept many lawmakers of color who are otherwise inclined to support the positions of the big phone and cable companies from opposing Net Neutrality — despite the financial contributions they receive from the industry.

By the time the FCC was set to vote, a broad coalition of public-interest and racial-justice groups had galvanized millions of people — not to mention President Obama — to urge the FCC to pass rules that would give the agency the legal authority to enforce real Net Neutrality.

And by February 2015, Chairman Wheeler had abandoned his initial industry-friendly proposal in favor of the strongest Net Neutrality rules in the agency’s history.

“We listened. We learned. And we adjusted our approach based on the public record,” said Wheeler. “In the process we saw a graphic example of why open and unfettered communications are essential to freedom of expression in the 21st century.”

An ongoing struggle

While we should celebrate this victory, the fight isn’t over. The ISPs will never stop trying to kill the open internet. In fact, they’re suing the FCC to get the rules thrown out in court and lobbying to pass legislation in Congress to overturn the FCC’s decision.

The struggle continues. It always does.

But for now, the open internet lives. And it enables racial-justice leaders to speak for themselves and be heard.

The ability to speak freely can be a revolutionary act that informs, inspires and influences a new generation of leaders to fight to prevent history from repeating itself in the effort to build a more just and equitable society.

Perhaps this growing political pressure will increase the presence and influence of people of color in the media industry. And perhaps it will change the media’s historical narrative when it comes to covering communities of color.

“If the internet stays a place where you can share your voice without impediments or limits then the discourse will eventually change,” says Varela of Latino Rebels. “It might not change in our lifetime, it might not change in my kids’ lifetime or my grandkids’ lifetime, but it will change.”